“We created a monster.”

That’s how SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son, whose company had invested billions into WeWork, described the situation at the company in November.

Over the last several months, various instances of questionable corporate governance on the part of the WeWork CEO Adam Neumann had emerged: from patenting the phrase “The We Company” and selling it back to WeWork for $5.9 million to making extended family members top executives in the company.

But the real monster, arguably, wasn’t Neumann. It was WeWork’s dual-class share structure.

A common arrangement among companies going public today, this structure gave the company’s regular shareholders one type of stock and its co-founder Adam Neumann another—one with 20 times the voting power. This gave him virtually complete control of the company’s direction.

The dual-class share structure was popularized by Google and has since been used by companies from Facebook to Dropbox to help founders maintain control of their companies. But not everyone is a fan. Some of the world’s most prominent asset managers and investor groups recommend restricting companies from using dual-class shares entirely.

To better understand the relative merits of companies with dual-class versus single-class stock, we reviewed the IPO valuations and market performance of the 50 highest-valued VC funded companies to go public in the last decade, segmented by whether they have dual- or single-class stock.

Of course, it’s impossible to show a causal link between a company’s share structure and its performance on the market or its valuation. But the research we’ve looked at suggests the hype around founder control might not be all it’s cracked up to be.

Download the venture report

Valuation at IPO

For all IPOs prior to 2019, dual-class companies tended to debut at higher post-money valuations than single-class companies, with 10 achieving a range between $2.7 to $80+ billion—Facebook, Snap, Groupon, Dropbox, Zynga, Workday, Fitbit, GoPro, Square and Pure Storage. Conversely, five single-class stock companies achieved post-money valuations of at least $2.5 billion at the time they went public: Twitter, Lending Club, Docusign, Palo Alto Networks, and Arista Networks.

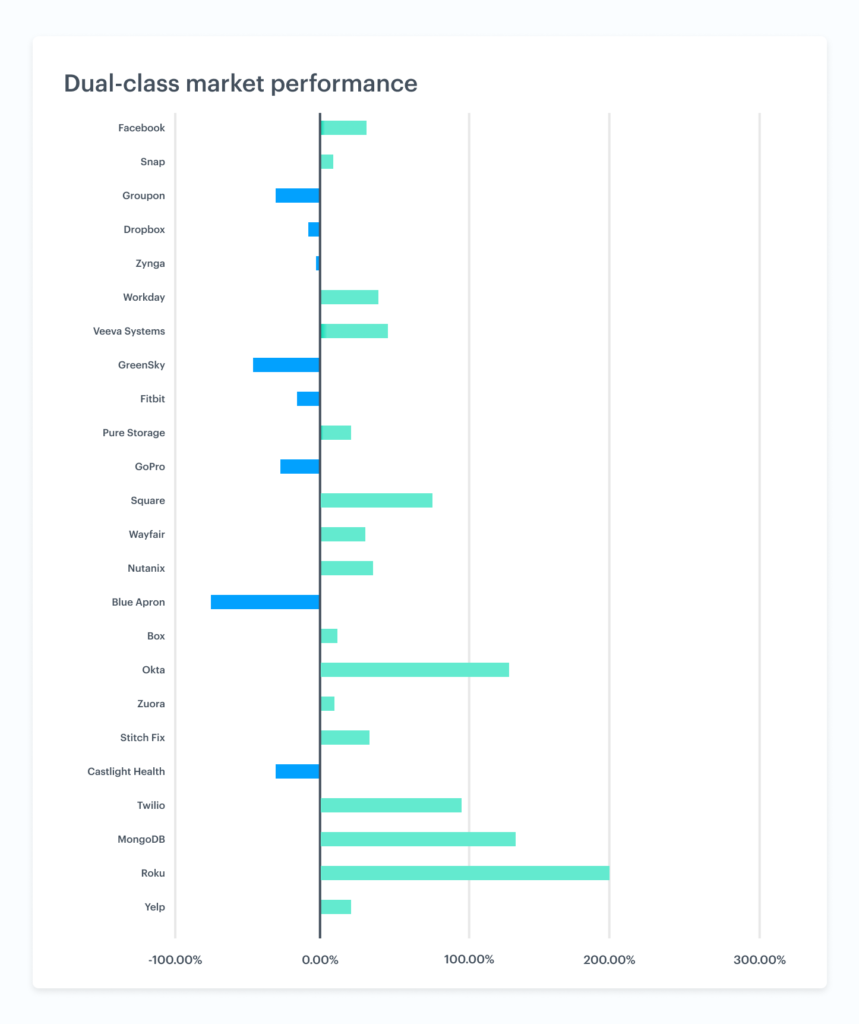

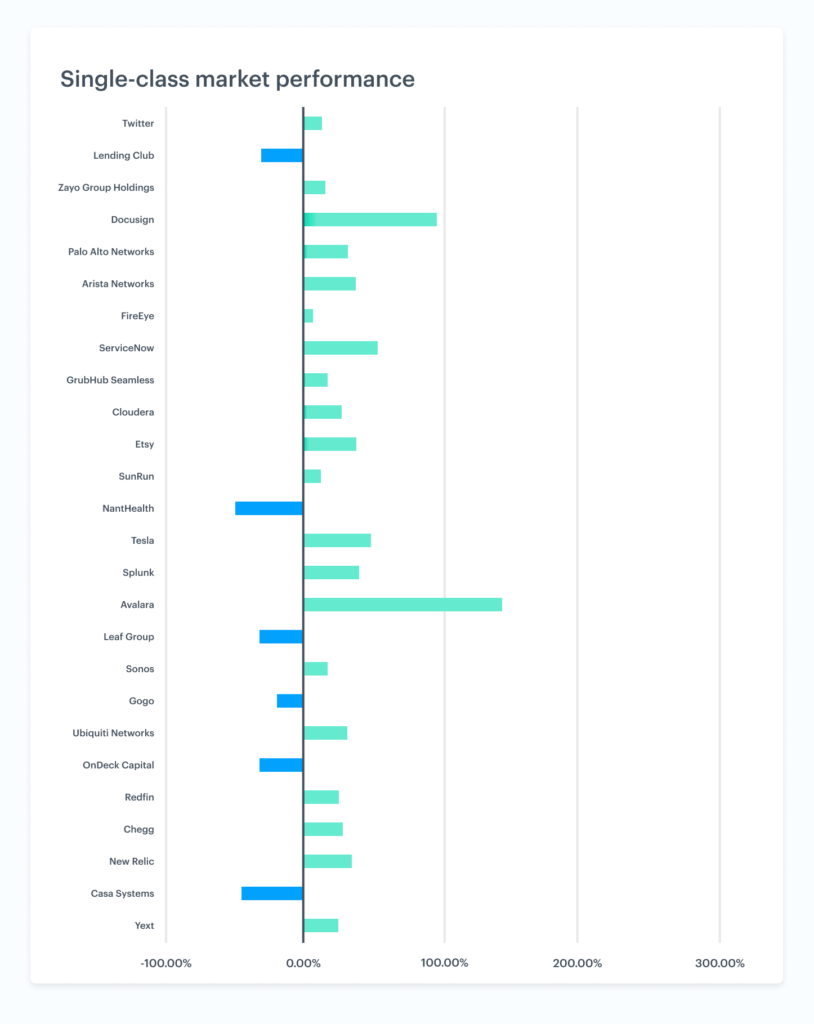

Average market capitalization

When we looked at the average performance of companies since IPO—across the entire company population—we found greater average growth among dual-class companies, but also a greater number of companies that have lost value since their IPO, with a third of dual-class companies performing below their offering price as of the end of 2019.

Among single-class companies, we saw slightly fewer losses, but also fewer with substantial gains. Of the dual-class companies we examined, eight businesses have lost value since their IPO. Three have surpassed 100% growth: Okta, MongoDB, and Roku. One—Roku—has grown by nearly 200%.

Our findings here align with research showing that companies with more aggressive growth models and unstable profits can often be better served by dual-class stock structures.

Of the single-class companies we examined, valuations for six have since dipped from their postings at IPO: Lending Club, NantHealth, Leaf Group, Gogo, Casa Systems, and OnDeck Capital.

Growth was more modest among single-class companies. Only one company surpassed 100% growth, tax compliance software vendor Avalara.

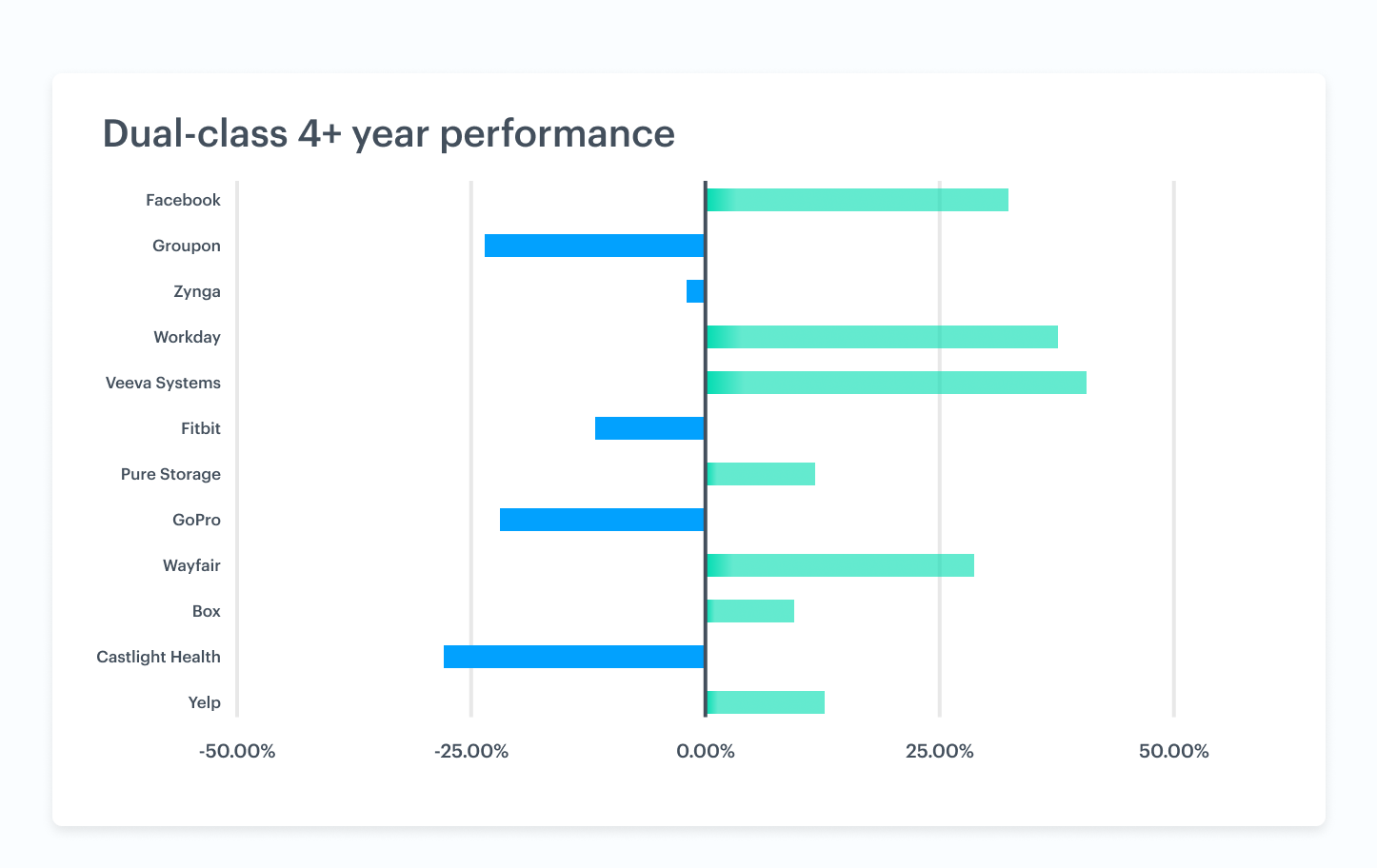

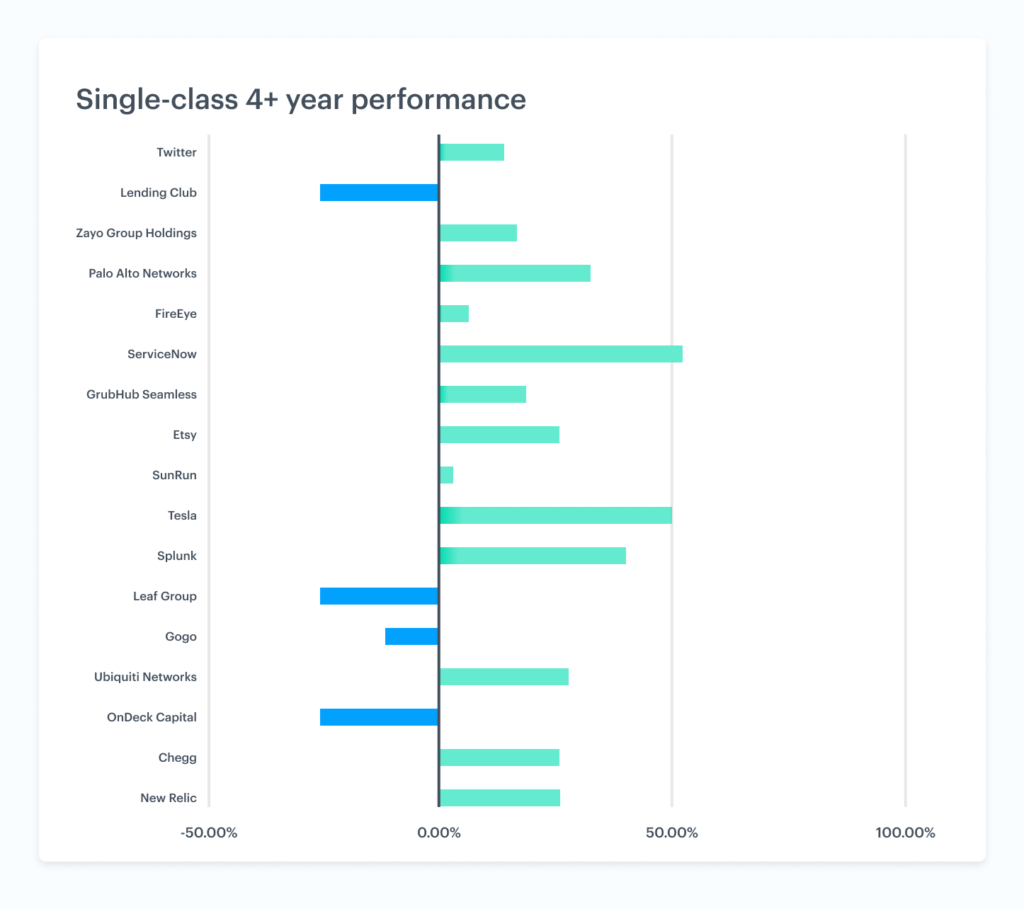

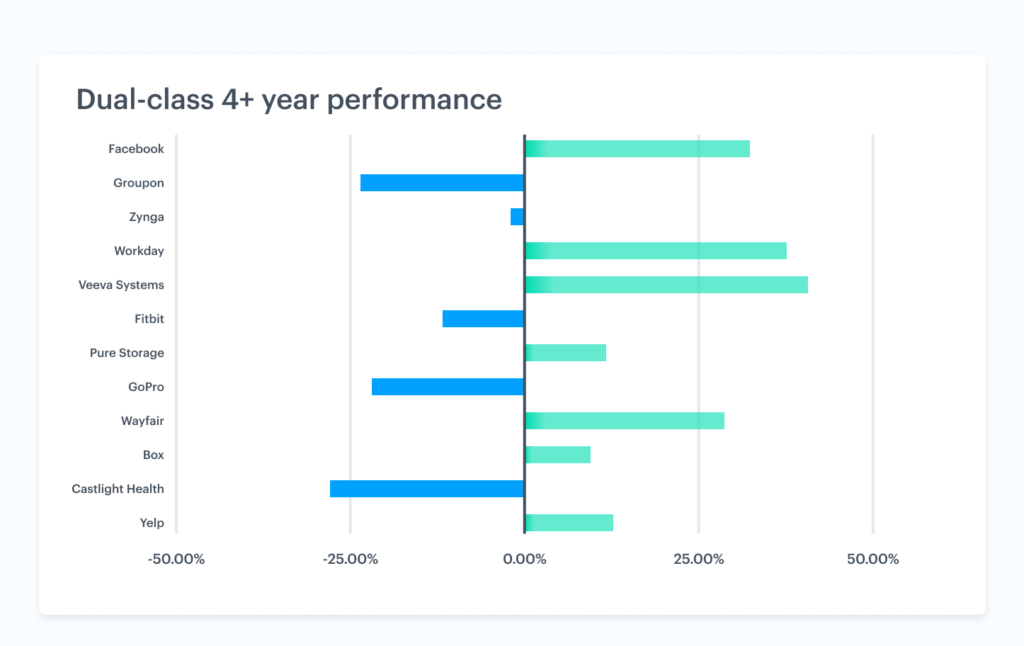

Long-term market capitalization

To keep our focus on the long term and post-IPO fluctuations, we also decided to exclusively analyze companies that have been public for at least four years. We found that over this period, 13 single-class companies demonstrated gains, while just four lost value: Lending Club, Leaf Group, Gogo, and OnDeck Capital.

For dual-class companies, performance over a four-year period was much more hit-or-miss. Among the dual-class companies we reviewed, seven gained value since their IPO. Five lost value during that period: Groupon, Zynga, FitBit, GoPro, and Castlight Health.

These findings comport with those of the literature on dual-class stocks — researchers have found that they tend to underperform single-class stocks. An SEC study found that companies with dual-class stock trade at a “perpetual discount.”

Long-term vision vs. short-term accountability

Dual-class share structures, the thinking goes, protect innovative and forward-thinking founders from the short-term pressures of Wall Street.

“[I] have voting control of the company, and that’s something I focused on early on …” Mark Zuckerberg said in recently leaked audio. “Without that, there were several points where I would’ve been fired.”

According to Google’s founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, their goal to “focus on the long term” was always incompatible “with the short-term sway of shareholders… more worried about quarterly profits.”

But they also create a power balance that diminishes the influence of shareholders. The Investor Stewardship Group, whose 50 members oversee $22 trillion in assets, is one organization that has called for a ban on dual-class stock—State Street, the world’s third-biggest asset manager, is another.

Of course, if dual-class structures were inherently worse than single-class, investors wouldn’t buy into the companies that use them. Still, there is a persistent mythos around the idea of the dual-class structure, a line of thinking that founders need to maintain control at all costs.

When it comes to performance on the public markets, we’ve seen some evidence that dual-class structures can be beneficial for some kinds of businesses. We’ve also seen evidence of single-class structures outperforming those companies in the long run.

In the end, our conclusion is that founders weighing the decision to go single-class or dual-class should think about their unique business, its needs, and its situation—not Zuckerberg or Google.

Note: A version of this article first appeared in PitchBook’s Q4 2019 Venture Monitor. All company financial and market capitalization data referenced in this article was sourced from PitchBookand Morningstar. Company selection was based on valuation at the time of IPO and includes only companies headquartered in the US that have been public for at least a year. Companies that did not accept venture funding were also excluded.